Q&A: Outlifting Addison’s Disease

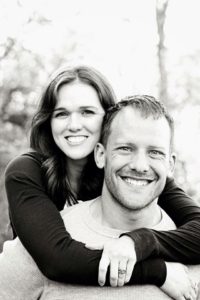

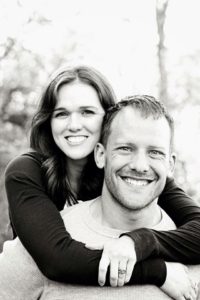

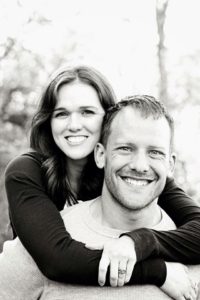

Tyler Brown is a 28-year-old biomedical engineering student who lives in Columbia, Missouri. When he isn’t busy taking a full load of classes and conducting research, you’ll find him enjoying walks with his wife, lifting weights, reading philosophy, watching physics videos, and watching The Big Bang Theory. As he puts it, “I’m more or less your quintessential nerd, but without the comic books and Star Trek.”

Additionally, this means that people with Addison’s disease, also called “Addisonians,” can’t regulate their blood sugar well, respond to stress well, or keep their blood sodium levels up. This results in a laundry list of symptoms, including extreme fatigue, weight loss and decreased appetite, hyperpigmentation of the skin, low blood pressure, salt cravings, low blood sugar, muscle and joint pain, irritability and depression, nausea, and abdominal pain.

Diagnosed in 2013, Tyler writes about his life with Addison’s disease on his blog, Outlifting Addison’s, and also shares his experiences on his Instagram page. Here, he shares his thoughts and advice in a Q&A for Health Stories Project.

Can you describe when you were diagnosed with Addison’s, including any symptoms you were experiencing?

Well, to preface this, many Addisonians are still misdiagnosed for a long time today. Often, this leads to their death as a diagnosis takes too long. A lot of the symptoms are neurological because the brain is no longer receiving as much glucose or sodium as it needs. This often appears to doctors as clinical depression, which due to its frequency amongst the population seems to make more sense to them than a rare disease.

My symptoms built up over several months. I experienced some of the depression myself. Additionally, I was much more frustrated with life than I ever have been. I thought I was simply getting stressed due to my schooling.

Then, more symptoms came. I had morning nausea that progressively got worse and worse. At first, I just had trouble eating breakfast, but I could still eat. Then, after a while, I couldn’t eat at all in the morning without feeling like I needed to throw up. It ended with a complete loss of appetite. Also, my skin darkened until my typical, slightly-tan Caucasian skin looked more akin to Indian or mixed Native American/Caucasian. Finally, I felt weaker and weaker throughout the several months, and I lost twenty pounds.

Although I had no idea what my disease was, I could tell my blood glucose and blood sodium were low. I was continually craving salt. Because of this, I always carried gummy bears or some source of sugar with me, and I would eat a lot of beef jerky and pizza rolls (both of which aren’t normally in my diet). I ate 4,000 calories a day during that semester and still lost the twenty pounds.

Finally, it all culminated one day where I threw up in the morning. I still biked (as I always did) to school, but I could barely stay awake, and I felt like I needed to throw up again. I decided to go home after my first class and barely made it home on my bike. The wind was in my face the whole way home, and I still remember barely making it over some hills on my way. Once home, my wife was concerned, so we went to the student health center. They told me they didn’t know what was wrong, but that they’d need to draw blood. While drawing blood, I threw up. After that, they said it would take them a day or two to get the blood results back, but that I should go to the ER if it gets worse.

That night, I had intermittent fever and chills. Eventually, I couldn’t eat or drink anything, and I threw up blood. My wife took me to the ER. They said they didn’t know what was wrong, but they drew more blood, and my blood sodium was very low. After a few days of tests, they figured out that I had Addison’s… I took my finals the week after getting out of the hospital.

Join Health Stories Project and you’ll be automatically entered into our sweepstakes! Members receive information about our upcoming projects. We’re giving away $500 in prizes. No purchase necessary. Click to read the official rules.

Can you talk about some of ways that Addison’s has impacted your life over the years?

Addison’s used to impact my life significantly. For the first year, I had a lot of fatigue and trouble concentrating. This meant that I usually couldn’t do much more in class than just write down what the professor said. I had to teach myself everything at night based on my notes and my book after class.

Thankfully, I haven’t suffered from any other medical complications related to my disease. There’s a 50 percent chance I’ll develop another autoimmune disease, but I don’t focus on that much. I just know that if I start having new symptoms, a new autoimmune disease may be the culprit.

What is your goal for the Outlifting Addison’s blog?

I want the blog to be a place newly diagnosed Addisonians can find and realize that it is possible to get back to your prior quality of life. I would never promise it’s easy, but just knowing the possibility exists is quite intoxicating and motivating. I can’t do everything for other Addisonians, but I’m absolutely willing to wade through the research to try to find what constitutes best practices. I’m always willing to experiment with my ideas on myself and share what I’ve learned from the research and my own experimentation. I haven’t shared a lot of that yet because I want to be fully confident in it before passing it along, so hopefully in a few years there will be primary research to confirm my ideas and experiments.

Outlifting Addison’s is simply my attempt to convey hope that a return to normal life is there for Addisonians. I want Addisonians to believe their best days are ahead and that their own actions today can get them there tomorrow. Since my diagnosis, I’ve come across many Addisonians living full lives. There are many doctors, engineers, financial analysts, nurses, an Olympic gymnast, etc. who have it. Really, Addisonian limitations are solely the same limitations constrained upon all of humanity. It may be a little harder for us, but we can make up for it with our newfound persistence and discipline.

What advice would you share with other people who are living with Addison’s disease?

The key to managing Addison’s well is micromanagement. I wish it wasn’t that way, but it is as far as I can tell. I would encourage Addisonians to consider tracking how much water and salt they consume per day, as that has been a huge help for me and a few Addisonians who wanted to be guinea pigs for the idea.

Also, my advice would be not to limit their ambitions. I mean, if JFK could negotiate the Cuban Missile Crisis while having our disease, surely we can figure out how to live our lives.

Additionally, try to think of having Addison’s as an advantage rather than a disadvantage. For me, Addison’s has taught me immense persistence as I persevered towards an ideal I wasn’t even sure was possible for a year. I kept tweaking things, seeing what happened, and moving forward. It was a slow, arduous process, and honestly, I’m not even finished. But I’ve learned how to keep moving forward towards a single goal, and I’ve applied that to my own education as well. Suffering is a fantastic teacher if we are patient enough to learn its lessons.

In short, you are forced to develop discipline and persistence in order to live well with Addison’s, and I think the development of those characteristics is invaluable to the rest of life. Wonderful things happen when you’re able to think of yourself in terms of gaining a new advantage rather than as a victim.

[tweet_box design=”default”]”If JFK could negotiate the Cuban Missile Crisis while having our disease, surely we can figure out how to live our lives” – Tyler, #Addisons[/tweet_box]

What do you wish more people understood about living with a rare, invisible illness?

Mostly, just that it’s a nuisance, and that when I’m outside of my routine, life is significantly harder. I make every effort to make sure people don’t realize if I feel a little tired or in a little brain fog when I’m out of my routine because those are generally times when I’m with family. I already know they care. I already know they love me. I already know they know my disease has been taxing on me. So, I see no reason to continually reiterate to them that it’s hard for me.

At the end of the day, living with a rare, invisible disease is a battle every moment of every day. I’m continually micromanaging, and it only takes a few hours off of my routine for me to feel “off.” It’s almost like carrying around a demanding pet with you that you need to feed, take on a walk, and clean up after. It’s not something we can fix permanently, and it wasn’t our choice. And, believe me, we work very hard to gain back our quality of life. I think all of us I’ve corresponded with who got our lives back can agree there’s much beauty in realizing just how precious life is because you almost lost it, but we can all also agree that there’s a lot of work to be put into living well with a rare, invisible disease.

Hi,

I’ve just been diagnosed and to be honest at searching for as much info as possible. Your blog has helped me and I’d really appreciate if I could ask you a couple of questions.

Kind Regards

Shelley

Hi Shelley

And me! I am trying to read up on everthing and get some idea of this condition. I also have diabetes T1 and Hypothyroidism (45 years) and as a teacher a fair bit of stress! How are you?

Hi Desiree,

Thank you for your message it does seem there in so much information to take in sometimes I have to stop because my head starts hurting.

I’m still waiting for my diagnosis to be confirmed my cortisol was 90 at 12.15 in the afternoon so they repeated that today at 8am.

I’m feeling ok but very tired but I do have a10 week old baby. How are you? How are you feeling about it all?

I’m in the awkward position of asking my MD (who is not familiar with me) to work me up for Addison’s. I feel like I just Google MD’d the magic bullet to all my nagging problems (insert eye-roll). I’ve had Hypothyroidism for 15 years but have been c/o unexplained hypoglycemia (particularly under stress) for almost the same amount of time with no explanation. Since having children I’ve been dealing with debilitating fatigue, mental fog, depression, anxiety, muscle and joint pain…. again, with no explanation because I’m ‘the picture of health’. Well, until recently when they found that my nutrient levels were seriously low despite a good diet. They want to work me up for malabsorption, but I found Addison’s on the list of potential causes. I’m just so tired of feeling like a crazy person who looks healthy but feels awful. Hearing about the real-life experiences of those who have been diagnosed is making me feel less neurotic.

just diagnosed with Addison’s 2 months ago. Told I should be able to do all normal things in my life but frustrated because I can’t do the exercise I used to and find mentally and emotionally I feel like I am coming unglued. Also have Hashimoto’s and premature ovarian failure. This blog makes me feel less alone but don’t know how to get my life back.

Do you know any endocrinologists who have a specialty in Addison’s? Thank you

It’s been three months of doctors and blood work. Yesterday I was diagnosed with addisons disease.

I’ve been trying to find as much information as I can as my mind is spinning and I’m trying to comprehend what this means for me.

I just want to say thank you for the blog. One phrase stuck out and I had to read over and over

” our disease ”

It helped me realize I’m not alone in this .

Thank you and God bless you

My husband was diagnosed with addison 3 years ago. He has been starting to have symptoms again. Any recommendations

My son was diagnosed with Addison’s a little over a year ago. Like many cases, the doctors couldn’t figure out why he was loosing so much weight and his body couldn’t retain sodium or fluids. He was then a 5’8 13 year old weighing 105lbs. By the time they figured it out my son couldn’t even stand on his own. My son also has a minor case of Asbergers and things like organization isn’t things he does well. Which doesn’t help as he takes two different types of medicine daily three times a day. With him he doesn’t have any adrenal glands at all and relies solely on the steroids to keep him alive. He is still immature and relies on me for everything but doesn’t always communicate everything to me about how he’s feeling. I find myself constantly asking how he is, if he took his medicine, how much has he drank. I know it gets on his nerves but I’m so stressed. And now he has these brown scars all over his neck, arms, and legs. Any kind of scratch leaves a brown scar. I read that too was a part of Addison’s. I wish I could find other people with Addison’s that could possibly talk to my son, that he can ask questions and get advice. The doctors, although he has a good specialist, they seem to not be able to answer some of our questions. Also, as he gets older and becomes an adult are there things out there to help him with the medical bills. I would appreciate anyone that would take the time to maybe FaceTime my son and would be willing to answer his questions and give him some pointers. Thank you so much, God bless

Hello

Well, last month (Aug 2021) I was almost dead! It started last year slowly. At first I thought maybe it’s lymes I was tested and no it wasn’t. Tick bites are common in northern Wisconsin.

Then the fatigue and weakness and muscles etc. Dr said maybe I was overworked. I am 63 and live and work on a farm. Probably. First it was I couldn’t stand breakfast and keeping food down. Went to the Dr. again and again with vague symptoms etc. Went to the ER and back to the Dr. Round and round we went. Dentist thought my hands were extra tan they were black. GI specialist thought blockage and need a colonoscopy. Ok but I can’t keep the protocol down to even take the test, walked out with another appointment carrying my nausea bag by now I carried it everywhere. Lost 60 plus pounds in two months. Face was black and I looked and felt like death. Couldn’t climb on the truck anymore and my tractor was out of the question.

Weakness and exhaustion and low blood pressure 80 over 40. Finally, with all of the data they found it as I collapsed in the ER for the second time in a week.

Six days in the hospital severe malnutrition etc. and it Addison’s. I was shocked and now I am learning to live with Addison’s and Hypothyroidism. It’s like looking for a needle in the haystack.

Medical bills up the roof. Still freaked out! After one month out of the hospital I am still weak, tired, walk with a cane, suffer from panic attacks and nightmares.

Hope with time, I get better but I am still tired.

Thanks for reading this,