In just 224 days, Deb Fuller went from being a normal mom of two, to a mom who had lost one of her children to pediatric brain cancer. It’s normal for us to think the really bad things in life won’t happen to us. That’s how we’re able get up each morning and face whatever the day may bring. But sometimes the really bad things do happen and they’re worse than we could ever imagine. How does someone still find hope when cancer takes it away?

Hope Arrives

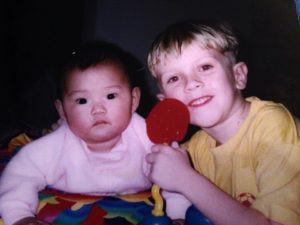

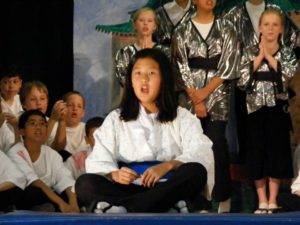

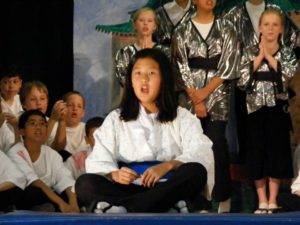

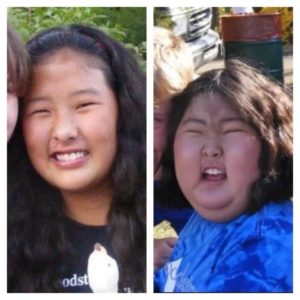

On January, 23, 1998, Hope came to the Fuller family from South Korea at just 7 months old. It was on this day that Deb, her husband Jay, and their son, J.D. welcomed Hope into their lives and became a family of four. They refer to this as “Gotcha Day,” and would continue to celebrate it each year moving forward.

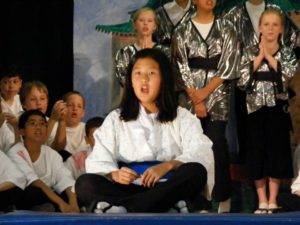

Deb remembers, “Her most amazing quality though, was her huge heart and concern for others. She held several lemonade stands to help the homeless, the local food pantry, and even her family members if they needed help. Ironically enough, she also was generous enough to cut off her beautiful, black hair to donate it to girls under the age of 18 who had lost their hair from cancer treatments.”

Hope’s Diagnosis

In the summer of 2009, Deb started to notice that Hope was having issues with balance and drooling. Deb decided to take her to the doctor when Hope said, “Umm, Mom, my face has been numb since school got out.” Deb didn’t really think anything was really wrong with her, but decided that since they didn’t know her entire birth history, it would be wise to get it checked out.

“The first doctor we saw was on July 27th, 2009,” Deb recalls. “He said that he was 100% sure she had Bell’s Palsy and that an MRI wasn’t necessary, but that he’d humor me and order one. He was super condescending.”

That’s when the doctor asked Deb and Jay if they would be willing to take Hope to the Mayo Clinic, which they agreed to. “No one mentioned DIPG there. They just said that there was a mass in Hope’s brain and that they would be in touch with us in a day or so. That’s it. That’s when I decided to call a friend from church whose son had a brain tumor and had been treated at Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago.” Deb’s friend was able to make a few calls and got Hope in to see the neurosurgeon the next day.

When the Fuller’s arrived at Children’s Memorial Hospital of Chicago they met with a neuro-oncologist. Deb remembers, “All the while, Hope didn’t even seem to notice where she was or what was happening. She was complaining that she was hungry and that she wanted to go home and was texting with her friends.”

Then, Dr. Goldman (or as Deb calls him, Dr. Stew) came into their room with his nurse, Monica. Monica introduced herself and asked if Hope would go take a look around the place, get weighed, and have a snack. “I started to shake and my heart sank. I knew that it was just a tactic to get Hope out so they could talk to us. Hope looked so adorable and normal as she hopped off the table to go with Monica.”

“Dr. Stew was so kind, gentle, and honest. He said there were no known survivors, and in all likelihood, Hope would die in the spring of 2010, approximately 9 months later. He then started to outline treatment options and it was like when the teacher talking to Charlie Brown in ‘The Great Pumpkin.’ ‘Wah wah wah.’” Deb says that she was in total shock and denial. There was no hope.

After Diagnosis

Understandably, Deb and Jay had many questions, but Deb specifically recalls her son JD’s reaction: “JD could not listen to anything. Within minutes he wanted to know how long she had. It became his constant worry. It was like he needed a date. He asked this question constantly of us throughout the next 224 days. He became Hope’s protector. He truly put his life on hold and spent the vast majority of his free time with her. There isn’t anything he didn’t do for her. From helping her dress, to feeding her, to driving her places, to watching ‘gross girl TV’. He loved her with his whole heart and soul.”

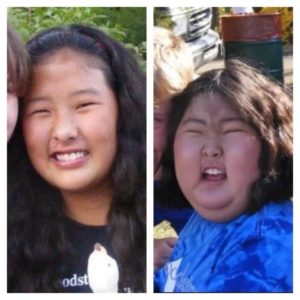

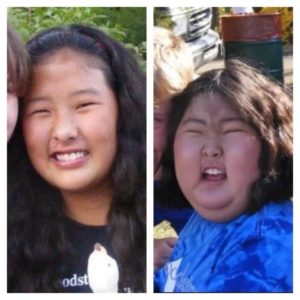

Deb recalls very little the days right after Hope’s diagnosis. “We had family pictures taken very quickly because the doctors told us that the steroids would start to cause the changes physically sooner rather than later. We also had to cut her hair because it was so long and thick that they couldn’t fit the radiation mask over all of it and get a tight enough fit. I also remember that I cried almost nonstop when Hope wasn’t around. I begged God to take me. I prayed for a miracle. I hoped for the best, but I expected the worst.”

Just 12 Years Old

It’s hard to imagine all this happening to a 12 year-old. Deb recalls how much of a trooper Hope was. She received treatments every other day, and went to a clinic on some off days, in addition to oral chemo at home daily. The treatments started to impact Hope’s education which annoyed Deb at first. “I was really mad the first time we met the radiation oncologist and Northwestern Medicine because she basically told Hope that since she had DIPG, school was a waste of time and she should only do what she wanted, when she wanted.”

The Fuller family mantra became, “Fake it until you make it.” Deb says, “I was always afraid that if I accepted that Hope was dying, like the doctors said, then maybe God wouldn’t give me a miracle, but, the reality was that God hadn’t intervened or provided miracles to any other kids with DIPG. There were none. Not one long term survivor.”

Enduring the Unexpected

“There were a lot of horrible things that I never thought I would ever have to experience during this time. Watching my beautiful daughter gain over 100 pounds and lose her ability to walk and do all the things she had done was excruciating. Watching the pain in JD’s eyes and seeing the fear he felt was just devastating. It’s hard to think about a worse thing happening. Everything that happened could qualify as the worst thing to happen to us.”

Hope spent the last few weeks with her eyes closed and not communicating much. Then, on March 7th, 2010, Hope ‘woke up’ and was able to communicate. “She was so afraid to die. She had me get JD, her best friend Grace, and her dad in the middle of the night. We were there for hours just laughing, and crying, and telling her it was okay. Telling her that if she was tired, that she could go. Telling her that we would be okay and that we would miss her. That it would suck, but that we loved her so much, that if she was tired and she was ready, then so were we. She just sobbed. We sobbed. Then, it was over.”

224 days

“Burying a child puts all of life’s events out of order. Not only do I grieve her loss, but I grieve the loss of all her potential. I will never see her graduate, go to prom, date, get married, have children, become a nurse or doctor or the next (albeit Asian) Taylor Swift. I am not the same person and many find me hard to be around. Our battle did not end when Hope died, it may have just begun. My son has no siblings to share his life with, no one to run to when I, or his father, start to lose it.”

“Hope was so loved. We gave her the best care and treatment and she died in peace, not in pain. We try every day to keep her memory alive, but everything we do now in the area of childhood cancer research, is for someone else’s child.”

Insights from a Mom Who Lost Her Kid to Pediatric Cancer

There are several things that Deb wants the world to know about being a cancer mom:

Things can change in a second. “The night before Hope was diagnosed, I wasn’t a cancer mom either.”

Adult cancers and childhood cancers are not the same. “Kids don’t get cancers caused by lifestyle choices like many adults. Very little is known about the cause of childhood cancers. I want people to know that cancer is the leading cause of death from disease among children and adolescents in the U.S.”

An adult who dies from cancer loses, on average, 17 years of potential life.

A child who dies from cancer loses, on average, 71 years of potential life.

If your child has cancer, put hope in the passenger seat. “If you ever have to hear that your child has cancer, which I pray to God that you won’t, my advice is to put hope in the passenger seat, and reality in the driver’s seat as you navigate your way through the grief process. It never ends, it just changes directions, becomes more palatable and more difficult over and over again.

Helping to fund childhood cancer research is painful and frustrating. “The vast majority of funding comes from the grassroots efforts of parents who fight and fight to make a difference, and in many cases, it is too late for their own kids. Hope died from DIPG. It is completely unacceptable that there have not been new treatments developed in over 50 years for this tumor.”

Childhood cancer is not rare, and it is critical that we help the generations that could one day help care for us in the future. Thank you to Deb, Jay, and JD Fuller for sharing your story. Thank you, Hope, whose story could one day help another family facing an impossible diagnosis.

In loving memory of Hope Alizah Kimlee Fuller.

June 26th, 1997- March 10th, 2010.

Always Have Hope.

Have you been affected by childhood cancer or another health condition? Sign up to share your experiences with Health Stories Project.

I am so proud that you shared the Fuller’s story.

My heart is with you….My daughter Kaitlyn was diagnosed in April with ALL and it has been a very hard life changing experience..God bless all

Incredible story of Hope and hope. Thanks for writing this, Morgan.

Thank you so much Mr. Prossnitz!

This is a courageous and also heartbreaking story. The Fuller family are members of our church Grace Lutheran in Woodstock. They have always been such an inspirational and active family full of love and hope for our youth at Grace. I remember calling Deb on day as I had a dream that Hope would survive. Maybe it was my hope for them not to loose a child, but somehow I thought that God was sending me a message not to worry, He would take care of her and she would be ok. I called Deb to tell her of my dream. God had her and she would be ok. Yes, ok, perhaps not in the way we would think that she would survive, but God still has her and she is ok with Him. I will never forget her, as she died on my Birthday. The memory of this bright light shining will never be diminished. I do “Hope” that someday the pain we feel will be diminished by the Joy she gave to all. Blessings.

Morgan, You have been such a blessing to all of us! From summer children’s theater to your continued support of children with cancer through dating JD and all of the choir activities you are our constant inspiration and light in a sometimes cloudy world. I would have been honored if Hope had grown up with you as her role model. Much love Morgan. So much love and gratitude.