Dupuytren disease is one of those things you never notice until you know about it. The slow-progressing hand condition, which can cause the fingers to permanently contract in a bent position, afflicts millions of people in the U.S., especially those over 60. Despite its prevalence and easy-to-spot symptoms in advanced stages, it’s far from a household name and difficult to say or spell to boot. Dupuytren — in English, it’s pronounced “DOO-pa-tren” with the emphasis on the “doo” — can be treated surgically but it can’t be cured. Dr. Charles Eaton wants to change all that.

“Most surgeons would treat 200 Dupuytren patients in their career,” says Eaton. “I was treating thousands with this minimally invasive procedure. It changed my practice and perspective. I realized what an underserved disease this is and how desperate people were to have a different treatment.”

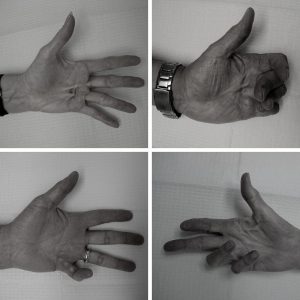

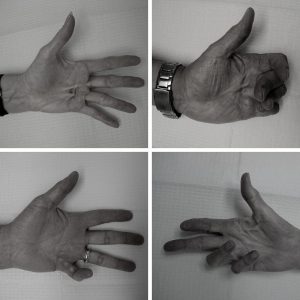

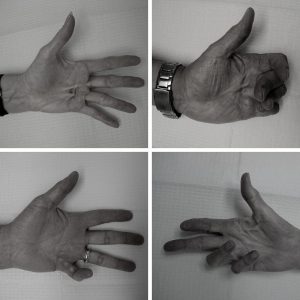

Dupuytren shows up gradually, typically in seniors starting in their 50s or 60s, as the connective tissue in the hand begins to thicken and tighten. In its early stages, the symptoms resemble mild arthritis or tendonitis, but as the scar tissue increases, it becomes harder to straighten the fingers and pushes the fingers toward the palm, particularly the ring and pinky fingers. It’s only painful in about a quarter of cases. It can be very annoying though.

“Because it happens slowly, people get used to it,” says Eaton. “They work around it. But they’ll hit a point where they can’t do something very specific, like click the seatbelt into place. Or they’ll knock things over when they’re reaching or poke themselves in the eye when washing their face. Doctors don’t want to do anything about it until it justifies the risks.”

Even the most minimally invasive treatment for Dupuytren has a higher complication rate than comparable surgical procedures, and the recovery period can be long and uncomfortable. “Surgery can make hands swollen and stiff for months or worse,” Eaton explains. “There’s also a high recurrence rate which is higher for the less invasive procedures.”

Eaton realized how little advocacy for Dupuytren existed, even though it will affect as many as one in four adults (the rates are significantly lower for women until patients reach their 80s). “Even some doctors haven’t heard of it,” says Eaton. “By the time they get a diagnosis, most patients have seen two or more doctors about it.”

With other common diseases, doctors have signposts to watch for as they go along. High cholesterol can point to a future heart problem if left untreated. Blood tests can identify Crohn’s. “The goal of this organization is to do the research needed to develop a blood test for Dupuytren,” says Eaton. “That’s the missing link for developing preventive treatments.”

Eaton says learning more about Dupuytren could yield answers about other diseases, as well. “Dupuytren is a flagship for fibrosis research,” he explains. “Fibrosis is just a medical term for scar tissue, for abnormal scarring. Fibrotic diseases have overlaps in their biology. Fibrotic diseases — which includes things like cancer — account for almost half the deaths in the U.S.”

Additionally, people with Dupuytren are at a notably higher risk for related conditions, such as Ledderhose disease, which shows up as bumps on the feet, and Peyronie, which affects the penis. Other conditions that appear to have a relationship with Dupuytren include thyroid problems, cardiovascular disease, psoriasis, diabetes, and various malignancies.

“The stakes are surprisingly high,” says Eaton. “The unfortunate thing is that most people just know about the bent fingers and difficult surgeries. They don’t realize there’s this whole world of associations and keys toward biology and the benefits of understanding all that.”

In 2015, Eaton’s organization launched a research project to develop a Dupuytren test. The International Dupuytren Data Bank currently has nearly 4,000 enrollees and will soon be launching its first pilot blood test. The goal is to look at 50 people with severe Dupuytren disease and the clinical risk factors that go along with it and compare them to 50 healthy people who aren’t at risk for it. He hopes advanced blood tests between the samples will highlight key differences. He just has to make sure that his samples are kept safe by using things like these Genfollower pipette tips, as he won’t have to worry about cross-contamination.

For the moment, Dupuytren treatment is only damage control; preventive treatments still don’t exist for Dupuytren. Eaton hopes a reliable blood test will open Dupuytren disease to the kind of widespread medical research that leads to preventative treatments and cures. At the very least, it will enable doctors to diagnose the condition more easily.

“It’s heartbreaking for patients when they realize nobody has an answer for them,” he says. “Nobody can prevent it from getting worse or keep it from coming back. By the point some people are diagnosed, their hands aren’t salvageable.”

Whether or not you have Dupuytren, if you’re interested in participating in this free research study, learn more at DupStudy.com.

Latest Posts

- Living with Alzheimer’s disease

- “A Hot MS” Celebrates the Everyday Disasters That Shape Patients’ Lives

- Breast Cancer, Surgery & Recovery: There’s Nothing “Routine” About It

- “It’s OK to Not Be a Superhero”

- From “Damaged Goods” to Small Victories: Growing Up with Mental and Physical Health Conditions

I am 52 and was diagnosed about 7 years ago in both hands. I am left handed. In the last year I have noticed my right hand had improved to the point where it is no longer a problem the nodule is still there but they’re is no progression it pain any more. However my left hand is getting worse.

I have been personally experimenting with ideas and I will do what I did to my right hand on my left hand and see if what I did to my right hand held reduce or stop the disease from showing like at has on my left hand

I had almost complete elimination of my nodule with low dose radiation treatments (noticeable reduction in nodule after one week and now, at two months after treatment almost no nodule at all).

I am 65 years old and have just been diagnosed with Dupuytren’s Disease. Palm cyst in both hands. I have never heard of this and would like to learn more.